Anna Teiche | A Secret I Keep from Myself

- Opening: Saturday, October 19, 7-10pm

- Exhibition Dates: October 19 – November 23, 2024

- Gallery hours: Saturday & Sunday 12-6 or by appointment

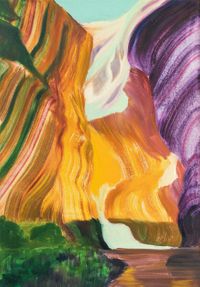

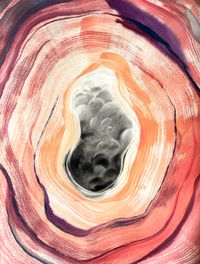

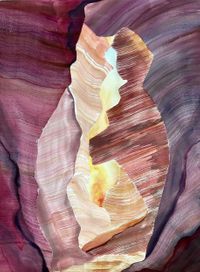

Anna Teiche’s work explores intersections between landscape painting, climate change, and illness. Her current body of work began in 2021, while caring for her partner while he underwent treatment for cancer. During this time, Teiche became interested in documenting connections between illness and environmental disasters. She uses abstraction and material experimentation across oils, gouache, and pastel to question what our eyes see — mirroring the uncertainty, disbelief, and confusion of an unexpected diagnosis. Each painting is a process of searching, a buildup of play and experimentation. Elemental land forms like volcanoes, caves, canyons and mountains often appear, representing an emotional range: The explosive to the slow burn, the uncertainty of smoke on a hidden horizon, drawing us closer while never revealing what lies ahead.

Bio: Anna Teiche is a painter based in Seattle, WA. She holds an MFA in Painting & Drawing from the University of Texas at Austin, and a BFA in Art & Design from California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo. Her work has been exhibited nationally in spaces including the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art (WA), The Visual Arts Center (TX), Cal Poly University Art Gallery (CA), and Unsmoked Systems (PA), among others. She has received project grants from the Dallas Museum of Art (2023), and Artist Trust (2019), and attended residencies including Vermont Studio Center, NES (Iceland), and Rockland Woods (WA).

_______________________

A Secret I Keep from Myself

Anna Teiche

I have been painting a lot of fires lately. I recently moved to Seattle, and the summer months here are alight with gorgeous sunsets, created because of smoke drifting in the air from Eastern Washington and Oregon wildfires. While the air quality is bad, the sunsets draw you outside to witness them, glowing, fiery pinks and oranges shifting to cool lavenders as the light fades.

When I was in graduate school at UT, my partner, now husband, was diagnosed with cancer. Unsurprisingly, this was one of the most difficult times of my life, the ambient, ever-present pressures of grad school, suddenly combined with life-threatening illness and caretaking responsibilities, put our lives in a new perspective. For a while, I stopped painting all together, because even that felt unimportant and unreachable. As Ben began chemotherapy, I began thinking about forest fires. Growing up on the West Coast, they were a constant, seasonal threat. I remember roadtripping through burnt, dry, seemingly dormant forest sites on road trips, seeing the toothpicks of charred tree trunks left behind, white bits of ash intermingled with the soil. The destructive aftermath of an all-consuming event. Watching Ben’s body transition through the stages of chemo held an eerie similarity — the total devastation that these drugs cause, the complications, the lack of control, and the slow regrowth in the aftermath. When Ben’s hair regrew, it came back curly, which I hear is a common shift for many chemotherapy patients. Just as when the forests slowly rebuild, they come back differently, saplings growing out of the trunks of fallen trees left in the fires’ wake, building new growth on the bones of the old forest.

During his treatment, I realized that it wasn’t that painting was impossible or unnecessary — it was, in many ways, what got me through his treatment in the end. The issue was that the way I was painting was impossible to return to. It was as if my brain had been re-wired, and my slow, repetitive, meditative process no longer made sense. I became fascinated with chance, with observing watercolor and gouache as it spread across a wet patch of paper, veins of color interacting with pools of water. Allowing chance into my once rigid practice felt necessary, because I was so suddenly confronted with the knowledge that everything was chance, that the unexpected could happen at any time, and to make art that continued to avoid this potential felt foolish.

My paintings transitioned into scenes of natural disasters, of landscapes transformed by chance and climate change and fire. I began to find ways to challenge my ability to control the brush mark. I started building big two foot wide brushes, that require my whole body to move across a canvas. I sought ways of painting that fully enveloped me, that distracted my mind from thoughts of illness and treatment and worry. Making a two foot wide brush mark took all the focus and bodily control I had — it was a moment of rest in an otherwise exhausting cycle of events. Later, I started building brushes out of Ben’s hair, that I had kept after shaving it off for chemo. The little curves and cowlicks of it creating unwieldy marks on the page. I became fixated on the surface of the canvas, mixing in collected piles of sand from my travels, building up layers of grit which would meet smooth, liquid layers of translucent paint, creating little topographies on the painting surface. Whenever I go somewhere new, I collect a jar of sand. I have built a vocabulary with it — each one offering a different grit and texture. The sand from Half Moon Bay, California — where I visited my brother to help him move the summer of Ben’s illness — has this really rough, chunky quality, while the sand from White Sands National park — visited on our dog’s first road trip with us — is fine, almost unnoticeable on the surface. The sand from a forest fire near Bend, Oregon – where Ben and I travelled with my family weeks after his chemo ended, worrying the whole time he might get sick — is full of ash and small pieces of charcoal that disintegrate as they mix with paint, tinting it with the grey-brown of ash. Each of these speak to a connection to place, and to a secret of sorts, a memory.

Ben’s illness made it so clear to me how connected we are to the earth, to cycles of birth and death and regrowth. My paintings have become composites of landforms turned bodily, the space and scale ambiguous, inviting forms that continually shift between larger than life and small, intimate closeups of the body. Horizon lines often hide what lies ahead, save for an ominous glow. They do not reveal what is coming next, but instead invite us in to study what is in front of us. The horizon is often a question, unresolved, in the same way that cancer has left a question in my family’s future — it is the sort of illness that, though luckily cured, never seems to totally leave our thoughts, never feels fully resolved, or clear, what the future will hold.

The title of this exhibition — A Secret I keep from Myself — is borrowed from Sheila Heti’s novel Motherhood. In it, the narrator is caught in this constant cyclical question, unable to decide wether she wants to have a child — worrying that if she chooses wrong she will be haunted by regret, and feeling that she is both completely unaware of what she wants, but suspecting that she knows the answer to this question, somewhere in her body, she just can’t access it. Many of these paintings begin as a secret. Often, they are painted over the bones of old paintings, the previous layer quietly influencing the painting’s surface, the buildup of material and color. They are bodily in process, and emotional in how they develop. I do not know where they will go as I begin, and rarely (if ever) do they come out as I predict. Each piece feels like a secret, slowly revealed if I listen hard enough.